This is an article from Slate online. (slate.com)

slate.com, jamelle bouie

I think it's worth reading. My formatting gets wonky 2/3 of the way through so if you want to finish just

select the link above.

Keep Hope Alive but how?

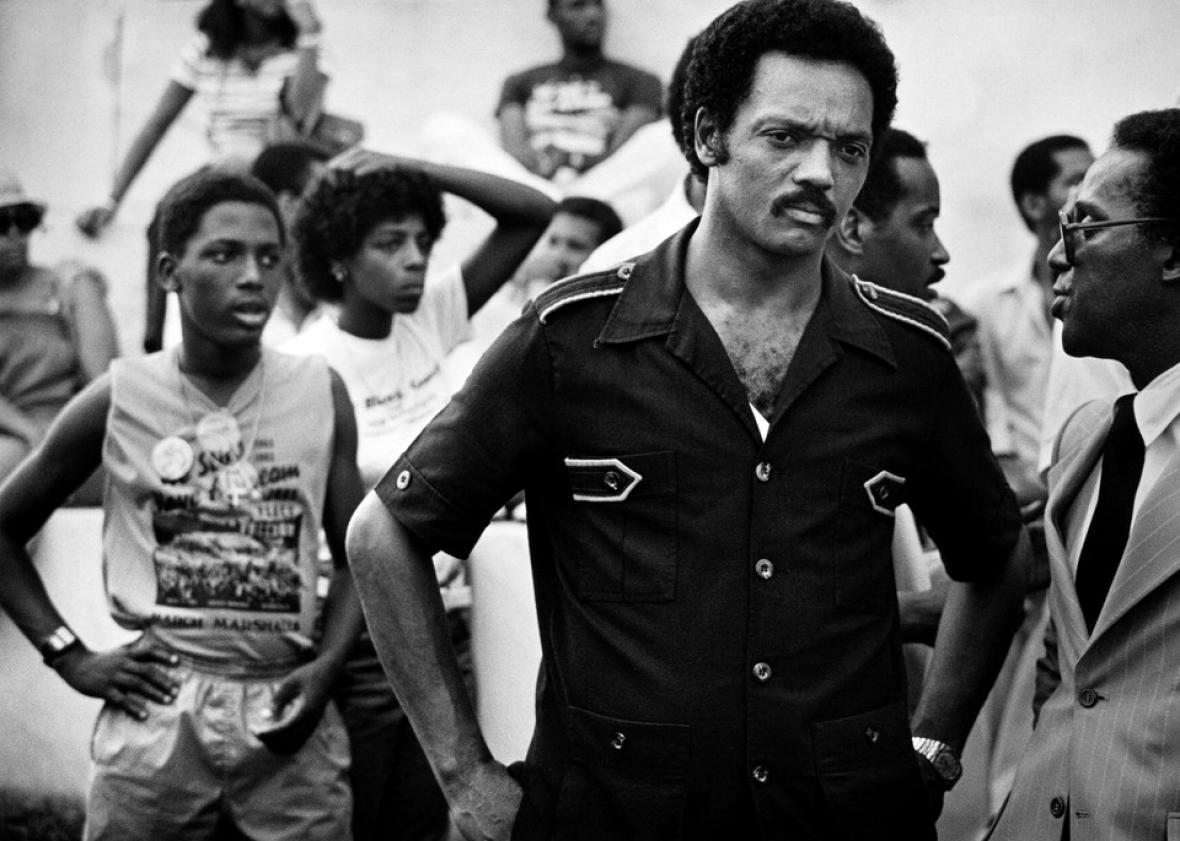

Demoralized Democrats have a road map for success in Trump’s America. It was written by Jesse Jackson.

Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

Jesse Jackson first ran for president during the national farm bust of the early 1980s. Debt for farmers had exploded from $85 billion in 1976 to $216 billion in 1983, with little relief in sight. As Jackson laid the groundwork for his 1984 campaign, the crisis had become so acute that he often found himself preaching his “populist Pentecostalism”—to borrow a phrase from biographer Marshall Frady—to large audiences of angry white farmers in the Midwest. It was an almost unbelievable circumstance for an unusual candidate who had to make unlikely alliances if he wanted national traction.

At a rally in 1984, some of those farmers arrived wearing paper bags over their heads, to obscure their faces. It wasn’t until later that Jackson learned they were trying to hide their identities from farm bureau officials. “I looked out there, all these guys in hoods. Sort of a little moment there,” Jackson recalled a few years later in a conversation with farmer and supporter Roger Allison, as recounted by Frady. “But our people have always had more in common than other folks supposed—right, doc? We’ve both felt locked out. Exploited and discarded. People saying about the family farmer exactly what they say about unemployed urban blacks, ‘Something’s wrong with them. If they worked hard like me, wouldn’t be in all that trouble.’ Fact, more you get into this thing, more you realize that black comes in many shades. We’ve found out we kin.”

* * *

In the wake of Donald Trump’s surprise victory, demoralized Democrats have had a fierce intramural argument over how to move forward. Most call for a renewed focus on economic disadvantage. But some juxtapose this with a push against so-called “identity” politics. “In recent years American liberalism has slipped into a kind of moral panic about racial, gender and sexual identity that has distorted liberalism’s message and prevented it from becoming a unifying force capable of governing,” writes Mark Lilla of Columbia University for theNew York Times. He urged a “post-identity liberalism” that would “appeal to Americans as Americans” with a press that would “educate itself about parts of the country that have been ignored.”

Lilla lauds Presidents Reagan and Clinton for their politics of shared identity and aspiration, which, if you’re attuned to the facts of those administrations, gives away the game. Reagan gutted federal civil rights enforcement, nominated judges hostile to the “rights revolution,” and elevated a conservative legal movement that, in the years since, has chipped away at the victories of the 1960s. Bill Clinton was an expert practitioner of identity politics, with a “shared vision” aimed at white Americans. As a candidate, he took steps to repudiate the black left. As president, he reinforced the trend toward mass incarceration and enshrined discrimination against LGBT Americans within federal law. To describe either Reagan or Clinton as exemplars of a “post-identity” politics is to submerge whiteness, maleness, and Christian belief as identities.

Robert R. McElroy/Getty Images

The fact of the matter is that Americans have never lived lives separated from the material facts of their identities. Jesse Jackson knew this. A liberalism that doesn’t, for example, engage with the specific problems of black workers or undocumented immigrants is one that can’t engage with “Americans as Americans,” if American is a stand-in for the citizens and residents who exist and not a euphemism for a certain kind of imagined American of decades past.

Even those who don’t make Lilla’s juxtaposition tend to silo questions and issues of identity from those of class and economic disadvantage. “Clearly there is no working with a president who believes in, or will bring forth, programs or policies based on bigotry, whether it is racism, sexism, homophobia, or xenophobia, and there can be no compromise on that,” said Bernie Sanders in arecent interview with GQ magazine. “But if Trump is prepared to work with me and others on rebuilding our infrastructure and creating millions of jobs, on raising the minimum wage, on passing Glass-Steagall, on changing our trade policies—yes, I think it would be counterproductive on issues that working-class Americans supported and depend upon if we did not go forward.”

To be clear, what Sanders isn’t doing isdismissing concerns of identity and representation. He clearly sees that they are important. At the same time, he wants to make a distinction between compromising on racist or sexist or homophobic policy and compromisingwith a racist or sexist political movement.That distinction doesn’t exist in practice.Bipartisan legislative victories bolster Trump and his administration, giving legitimacy to a movement centered on white grievance and white anger. Working with Trump to raise the minimum wage, for example, invariably strengthens a politics that casts Hispanic immigrants as a threat to national prosperity or paints Muslim Americans as a threat to national safety. Building new infrastructure doesn’t change Trump’s commitment to draconian policing. For black workers, then, the gains that come with new jobs are undermined if not vaporized by a larger agenda that endangers and disadvantages. A working-class politics that leaves black and brown workers vulnerable to white nationalismisn’t a working-class politics. It’s a white politics for white workers and counterproductive to broad advancement.

If inequality is shaped by place, gender, and race—which is to say, by identity—then any effective approach has to address those constraints in particular.

Because Sanders puts those questions of identity in a silo, he misses this relationship and risks being co-opted by Trump. At minimum he is pushing an incomplete populism that doesn’t grasp how the experience of class is inextricably bound up with identity.

In our conversations around inequality and poverty, we often miss a crucial fact: Not all inequality is created equal. On average, inequality and poverty among black Americans (as well as native groups and undocumented Americans) is of a different scale and magnitude than inequality and poverty among white Americans.

When white workers attain higher wages and greater economic status, they can translate this to better neighborhoods and stronger schools. When black workers attain the same, they can’t, at least not to the same degree. Middle-class status, insofar that black workers can reach it, is less stable and more tenuous for them than for their white counterparts. “Even if a white and black child are raised by parents who have similar jobs, similar levels of education, and similar aspirations for their children,” writes sociologist Patrick Sharkey in his book Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality, “the rigid segregation of urban neighborhoods means that the black child will be raised in a residential environment with higher poverty, fewer resources, poorer schools, and more violence than that of the white child.” Opportunity itself is redlined.

Black and white workers face the same kinds of economic disadvantage: deindustrialization, an eroding safety net, weak wage growth, and poor investment in needed infrastructure. But black workers (and other nonwhite workers) face additional challenges that move their disadvantage from a difference of degree to a difference of kind: residential segregation, discrimination in jobs and housing, and discrimination by lenders and banks, which in turn contribute to unfair and draconian policing, poor and unequal schools, and heightened exposure to impurities in air and water. They need specific and universal solutions. They need a politics that addresses all material disadvantage, whether rooted in class or caste.

* * *

In his 1988 speech to the Democratic National Convention, the “Keep Hope Alive” speech, Jackson provided a model for a Democratic politics that balances all of these concerns—that takes identity and class seriously, that understands their relationship and interplay, that appeals to common identities and forges responsive solutions. “Politics can be a moral arena where people come together to find common ground,” Jackson said, before moving on to an extended and illustrative metaphor.

When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, and grandmamma could not afford a blanket, she didn’t complain, and we did not freeze. Instead she took pieces of old cloth—patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crockersack—only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes with. But they didn’t stay that way very long. With sturdy hands and a strong cord, she sewed them together into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt.

Farmers, you seek fair prices, and you are right—but you cannot stand alone. Your patch is not big enough. Workers, you fight for fair wages, you are right—but your patch labor is not big enough.

Women, you seek comparable worth and pay equity, you are right—but your patch is not big enough. Women, mothers, who seek Head Start, and day care and prenatal care on the front side of life, relevant jail care and welfare on the back side of life, you are right—but your patch is not big enough.

Students, you seek scholarships, you are right—but your patch is not big enough. Blacks and Hispanics, when we fight for civil rights, we are right—but our patch is not big enough. Gays and lesbians, when you fight against discrimination and a cure for AIDS, you are right—but your patch is not big enough.

Each struggle, for Jackson, is part of a larger whole. He’s not making an individual appeal to black Americans or an individual appeal to white workers. He’s asking black Americans to see that their struggle is the struggle of white workers and vice versa. That higher wages and civil rights (and affordable education and programs for families) are inextricable. And to that end, Jackson proposed a broad agenda that linked material uplift for all Americans to a civil rights agenda, to the fight against South African apartheid, to the Equal Rights Amendment.

Jacques M. Chenet/Corbis via Getty Images

That vision grows out of Jackson’s biography. A veteran of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference who worked on the Poor People’s Campaign in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. A political organizer who worked to register voters and pressure politicians in both parties. An activist whose fights cut across class and race. Jackson gave a clear picture of his view in 1983, when he announced his first campaign for president, rooting his vision in the experience of black America but expanding it to include all marginalized groups.

This candidacy is not for blacks only. This is a national campaign growing out of the black experience and seen through the eyes of a black perspective—which is the experience and perspective of the rejected. Because of this experience, I can empathize with the plight of Appalachia because I have known poverty. I know the pain of anti-Semitism because I have felt the humiliation of discrimination. I know firsthand the shame of bread lines and the horror of hopelessness and despair.

For Jackson, a politics that cured inner cities and dismantled overcrowded ghettos was also one that rescued abandoned factories and deserted farms. It was a politics that, because of its focus on one of America’s most maligned groups, radiated outward to everyone who has struggled for dignity and recognition. Under Sanders’ rubric, identity and representation are separate from the question of a broad-based politics. “Yes, we need more candidates of diversity, but we also need candidates — no matter what race or gender — to be fighters for the working class and stand up to the corporate powers who have so much power over our economic lives,” he writes in a recent post for Medium. In Jackson’s vision, by contrast, identity and representation are critical. They ground a broad appeal that is attentive to lived experience, that stresses common threads without losing sight of the challenges facing each group, that sees diversity as integral to making progress on all struggles. This is a broad andinclusive liberalism—common vision from common struggle.

This approach would have real value today, not just because of its rhetorical niceties but because it connects to a concrete policy agenda. Writing in theAmerican Prospect in 2008, John Powell, now head of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at the University of California, Berkeley, argued for a new approach to targeting inequality and poverty. “Policies that are designed to be universal too often fail to acknowledge that different people are situated differently,” he wrote. “What is required is a strategy of ‘targeted universalism.’ This approach recognizes that the needs of marginalized groups must be addressed in a coordinated and effective manner.”

Yann Gamblin/Paris Match via Getty Images

It’s not enough to offer free college or a higher minimum wage. A higher minimum wage still leaves us with high structural unemployment in black communities. Free college still leaves us with vast inequality in public education. If inequality is shaped by place, gender, and race—which is to say, if it is shaped by identity—then any effective approach has to address those constraints in particular. But this doesn’t mean we have to sacrifice universalism. It means we have to tailor universal programs to those particular constraints.